Remembering Alison Winter

Alison Winter’s connections to the University of Chicago ran deep. In 1983, she came to the University as an undergraduate from Ann Arbor, where her father taught mathematics at the University of Michigan. He hoped she would major in science; she wanted to major in English literature. The compromise was history of science, but the compromise quickly became a passion. While at the University of Chicago she was mentored by, among others, James Chandler (Department of English) and Robert Richards (Department of History). Alison was determined to undertake further study in England and was awarded a National Science Foundation fellowship, among others, to attend Cambridge University in history of science. Alison received her Ph.D. from Cambridge’s Department of History and Philosophy of Science in 1993.

Alison Winter’s connections to the University of Chicago ran deep. In 1983, she came to the University as an undergraduate from Ann Arbor, where her father taught mathematics at the University of Michigan. He hoped she would major in science; she wanted to major in English literature. The compromise was history of science, but the compromise quickly became a passion. While at the University of Chicago she was mentored by, among others, James Chandler (Department of English) and Robert Richards (Department of History). Alison was determined to undertake further study in England and was awarded a National Science Foundation fellowship, among others, to attend Cambridge University in history of science. Alison received her Ph.D. from Cambridge’s Department of History and Philosophy of Science in 1993.

Alison returned to Chicago in 2001 where she was appointed associate professor in the Department of History and in the Committee on Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science. Alison was dedicated to supporting the next generation of scholars, producing several Ph.D. students and mentoring numerous post-doctoral fellows in the Clinical Medical Ethics program. Her devotion to undergraduate teaching in history of medicine, in film, in gender studies, and in Victorian literature won praise from students, many of whom became lasting friends. Both students and colleagues delighted in her genial and witty style, which she maintained even when engaged in pointed intellectual exchange. Her research won her several prestigious fellowships, including a Guggenheim in 2002. She was awarded The Gordon J. Laing Award from the University of Chicago Press for her book, Memory: Fragments of a Modern History (Chicago, 2012).

Alison Winter Lecture Series Events

“Signs of the Times,” Jim Secord, 5/6, 4:30pm

The early nineteenth century witnessed a transformation in communication technologies and public attitudes towards science. In Britain, the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (1826-1846) prospered at this critical juncture. One result was an outpouring of comic images caricaturing ‘the march of intellect’ and ‘the schoolmaster abroad’. Reproduced today on everything from coffee mugs to academic dust jackets, these images risk becoming stereotypical icons of a particular view of the period, in which enterprises like the SDUK are seen to have failed. Yet at the time they were published, these caricatures were ambiguous indicators of concerns over new forms of knowledge, often with highly specific references to contemporary books and events. As part of the play of fashionable talk in the culture of the salon, they sparked lighthearted banter, flirtation, discussion and debate.

James (Jim) Secord is Emeritus Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Cambridge, a Fellow Commoner at Christ’s College, Cambridge, and a Fellow of the British Academy. He has published many books and articles on the history of science during the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, including Visions of Science: Books and Readers at the Dawn of the Victorian Age (OUP, 2014) and Victorian Sensation: The Extraordinary Publication, Reception and Secret Authorship of Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation (Chicago, 2000), an account of the public debates about evolution in the mid-nineteenth century and winner of the Pfizer Prize of the History of Science Society. Other publications include Controversy in Victorian Geology (Princeton, 1986), editions of works by Mary Somerville, Charles Lyell, and Robert Chambers, and selections of Darwin’s Evolutionary Writings for Oxford World’s Classics. From 2008 until its completion in 2022 he was Director of the Darwin Correspondence Project. He is currently completing a book on the historiography of science.

Karuna Mantena, “Gandhi and Late Victorian Radicalism,” 2023-24 Alison Winter Lecture

“Gandhi would have been Gandhi even without Thoreau and Tolstoy.” Albert Einstein’s quip succinctly captures a persistent dilemma about tracking the intellectual origins of Gandhi’s political ideas – especially the origins of satyagraha or nonviolent resistance. Scholars are not only divided on how to weigh the “Western” versus “Indian” provenance of Gandhi’s ideas, but the very question is saturated by assumptions about Gandhi’s intellectual sophistication and/or originality as a thinker (or lack thereof). This lecture revisits the formative role of late Victorian radicalism on Gandhi’s politics and political thought to track more precisely the influence and legacy of movements like vegetarianism and thinkers like Tolstoy and Thoreau. In so doing, I hope also to show that in Gandhi’s case especially, the origins/influence paradigm should give way to a mode of reconstruction that foregrounds formative conjunctures of theory and practice.

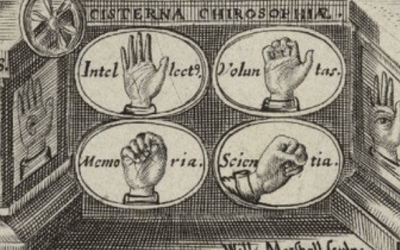

Alison Bashford, “Reading Modern Hands,” 2022-23 Alison Winter Lecture

Alison Bashford Laureate Professor in History and Director of the Centre for History & Population University of New South Wales "Reading Modern Hands: The Disenchantment of Palmistry" Introduction by Fredrik Albritton Jonsson 27th April, 2023...

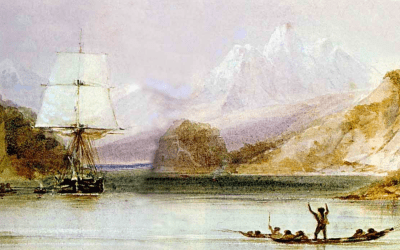

Ian Duncan, “Darwin’s Human History,” 2021-22 Alison Winter Lecture

2021-22 Alison Winter Lecture Ian Duncan (Professor and Florence Green Bixby Chair in English, University of California, Berkeley) “Darwin's Human History”

Mary Poovey, “Modeling and Its Discontents” — 2018-19 Alison Winter Lecture

2018-19 Alison Winter Lecture Mary Poovey (Emeritus Professor at New York University / Cultural Historian and Literary Critic) “Modeling and Its Discontents”

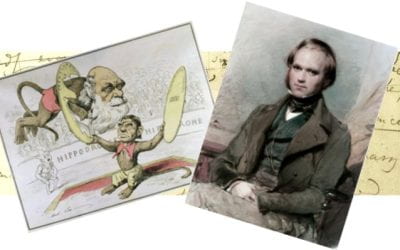

Janet Browne, “Darwin’s Afterlives: Recollection and the Making of Biography” — 2017-18 Alison Winter Lecture

2017-18 Alison Winter Lecture Janet Browne (Aramont Professor of the History of Science, Harvard University) “Darwin’s Afterlives: Recollection and the Making of Biography”

Simon Schaffner, “Time Machines and Memory Devices: Powers of Mind and Modern Histories” — 2016-17 Alison Winter Lecture

2016-17 Alison Winter Lecture Simon Schaffner (Professor of History of Science, University of Cambridge) “Time Machines and Memory Devices: Powers of Mind and Modern Histories”