Earth, Water, Fire, and Britain: Mapping the 19th-Century Empire of Things – A Conversation with Nicholson Grant Recipient Tyler Lutz

Tyler Lutz (Ph.D. Candidate, English) received a Nicholson Grant to do archival work in London during the summer of 2023 as part of his dissertation research concerning maps and the aesthetic dimensions of Empire. The Nicholson Center sat down with him to discuss his project.

You travelled to the UK for research last summer and spent a lot of time looking at old British imperial maps from the 18th and 19th centuries. Why maps?

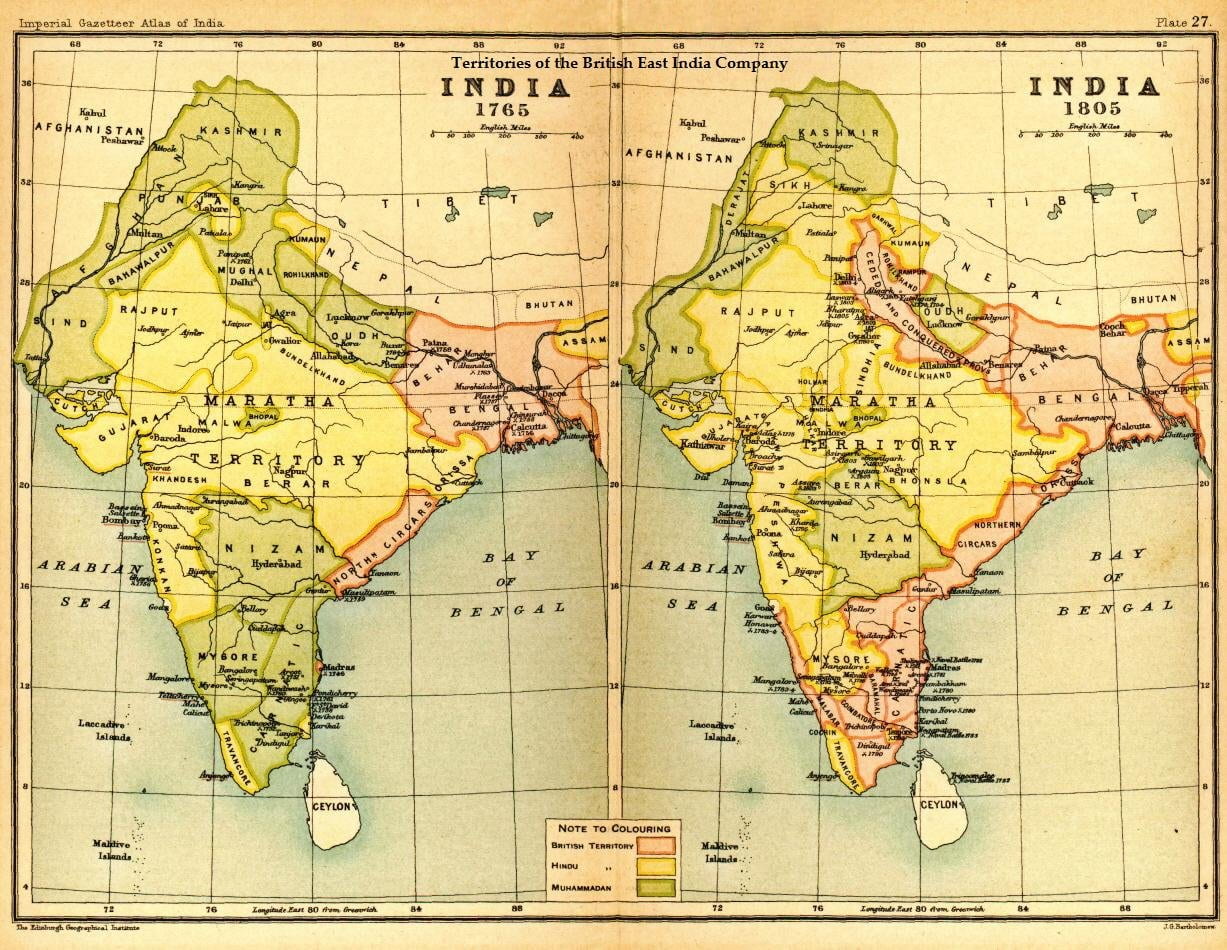

Maps are deliciously Janus-faced. Reading them requires remarkably little training; in many cases one needn’t even speak the mapmaker’s native language to understand what her map is saying. Their rhetoric, in other words, is consummately mimetic. But this simplicity is deceptive; maps are among the most technically sophisticated means of spatial representation imaginable. Even to do something as seemingly banal as drop a pin on our current location, our phones have to not only communicate with a sprawling array of satellites hurled into orbit around the Earth, but also perform a calculation in general relativity, accounting for Einstein’s discovery that time itself slows down in the presence of a gravitational field.This duplicity is not a recent phenomenon. My work centers on how maps created for the British East India Company and, later, helped the Raj negotiate and manage the two opposing faces of their maps’ seeming self-evidence, on one side, and their profound material and technical entanglements on the other.Contrary to those historians of cartography who take empire for granted and consider how these maps operated in its service, as a student of literature I pursue the converse tack: I posit that it is within the aesthetics and visual rhetoric of maps that the underlying parameters of empire were defined and constantly renegotiated.

So maps can help elucidate not only the political and ethical dynamics of imperialism, but the aesthetic dimensions as well. Why is aesthetics a necessary axis for the study of imperialism? What does it help reveal?

I deploy a minimalist definition of aesthetics as the sum of everything not on the page that nevertheless structures our relationship to what is. In Wittgensteinian terms, this corresponds to any move one could make in the language game initiated not by the question “what do you see?” but rather “how does it look?” Cartographically, a map’s aesthetics are thus most manifest in its blank spaces: on what we see when we have nothing in particular to look at.My project begins with the observation that something curious happens to the status of the cartographic blank space over the course of the nineteenth century. Eighteenth-century imperial maps deploy two nominally distinct rhetorical modes, which I refer to as “charting” and “mapping.” The former asserts that everything plotted on the chart represents some aspect of the real world, while the latter claims that all the relevant features of the real world within the map’s purview (e.g. all the mountains in the region, if it’s a topographical account) find representation on the map. Each mode imputes a distinct meaning to the blank cartographic substrate; for the chart, “empty” space denotes an absence of knowledge, while for the map it asserts a positive knowledge of absence.Nineteenth-century cartographic objects freely mix and conflate these two rhetorical modes, rendering the status of their blank spaces constitutively undecidable. I argue that this undecidability does generative work for the map in furnishing a phenomenologically distinct spatial aesthetic, upon which British empire comes to predicate itself later in the nineteenth century.I argue against critics who understand cartography’s complicity in empire as inhering primarily in the one-two punch of selective erasure of indigenous geographies (which the British accomplish by casting their charts as maps: as if to say “what I see is all there is”) followed by their marshaling of geographic knowledge to subdue populations in lands the British laid no claim to—couching the totalizing pretenses of their maps within the ostensibly neutral cartographic form of the chart. This bipedal line of reasoning relies on essentially eighteenth-century natural scientific understandings of blank space. The underlying image is that of a vacuum demanding to be filled: and if not by “enlightened” British colonial institutions, then by what else?But something vastly more interesting is happening in the nineteenth century. Maxwell’s description of electromagnetic fields and cognate developments in nineteenth-century physics enable the British to understand ostensibly empty space as not only having determinate properties but also as being able to support tremendously sophisticated and nuanced structures of being and transmission (e.g. light waves, in Maxwell’s case). In this context, I argue that rather than imaginatively emptying space in order to fill it, British empire is predicated on the obverse project: of filling space in order to empty it—that is, of structuring its emptiness in a aesthetically determinate way.We know from everyday experience that “empty space” is a logical contradiction. We can only haptically experience the blankness of space by filling it with our bodies—thereby paradoxically rendering it an empty space no more. Imperial maps function analogously, putting this contradiction to work; they fill space for the sake of evacuating it, manufacturing and magnifying the phenomenological emptiness of everything in between.The intense acuteness of this emptiness is precisely what nineteenth century imperial cartographies create by prompting us to simultaneously imagine the possibility of their spaces being filled—the empty chart’s “I don’t know what’s here”—and that of their ontological evacuation—the map’s “there is nothing here.”

If aesthetics can reveal modes of imperial justification, perhaps their study can sharpen our critiques of imperialism as well. Do you think your project can contribute to such critiques? How so?

The basic contradiction of British empire is that it consistently styled its own brutal structures of colonial oppression under the guise of progressive, enlightened liberation. Conventional critiques of empire treat this as a logical contradiction and conclude that one or more of its underlying terms must be false: either the British were fundamentally bad actors hiding behind good ideas, or essentially well-meaning global citizens caught in the thrall of ideas not actually as liberatory as they thought. While these critiques may well have rendered a positive service in the decolonial movements of the 20th century, it’s fair to say their edge has considerably dulled in the 21st. Consider how ineffectual they have been in mitigating the conflicts currently structuring our geopolitical landscape—many of them the revenants of British imperialism of centuries past: from Palestine to Kashmir to Hong Kong and its abutting sea.To be more precise, though, the problem with these lines of critique is not that they have become dull with use but rather that they have become too sharp for their own good. They tend to cut both ways. By deploying these arguments, we place ourselves in a symmetrical position to the very colonial institutions we imagine ourselves to be dismantling: how could we ever convince our critics in turn that we ourselves are not in the thrall of stale ideas? not hiding our own ulterior, selfish motives?Understanding British empire as a fundamentally aesthetic project opens up new, and, I suggest, perhaps more fruitful modes of critique. To view the tensions constitutive of this aesthetic as merely logical contradictions is to evacuate their force. This might at first seem politically compelling but it nevertheless deprives us of a nuanced understanding of the affective machinery by means of which empire was prosecuted.One of the conclusions my project draws is that British direct rule in India assumed the paradoxical form of what I call a “terrestrial thalassocracy.” That the Raj was a land-holding empire styled on maritime control; that it oppressed and (rhetorically, at least) “liberated” at the same time are not mere lies, logical aporias, or faults of the imperial system: they are at its motive core. The harder we try to reason away these contradictions, the farther we remove ourselves—and our criticism—from a meaningful engagement with empire, articulated throughout its undergirding aesthetic machinery.To view the British empire as an aesthetic project prompts us to explore avenues of critique beyond right and wrong—in both normative and epistemic senses—but instead in terms of the failures of its aesthetic ambitions.

Maps certainly seem to be one key place to get at these aesthetic dynamics. Do you plan to supplement your study of maps with other kinds of materials?

Imperial maps did not exist in a media vacuum, nor were they the only rhetorical genre interested in depicting spatial relations. As someone primarily trained in literature, I’m keen to examine how ideas about blank spaces and continental interiors operated and evolved in the self-consciously literary texts of the period. I’m especially interested in how visual and textual modes of spatial representation interfaced with each other.At the moment, I’m charting how place names occur in nineteenth-century fiction published in Great Britain and in the subcontinent. The primary centers of European colonial power in India were, for historical reasons, focused on port cities—primarily those we know as Mumbai, Chennai, and Kolkata. By plotting how these and other coastal cities differentially show up in literature relative to other places in the continental interior, I’m hoping to better understand how and when British empire in India transitioned in the literary imaginary and broader public consciousness from a primarily maritime enterprise to a fluidly continental rule.